It’s the first line of the fourth verse of an early 17th-century

Lutheran chorale. The most famous setting is by Bach in cantata BWV 48, and it’s

one of the most profound Bach chorale settings.

The theology underlying the verse is horrific (hence the unusual

setting), so let’s just say that the line itself translates roughly as “If it

must be so …”. (The full translation

takes us directly into Lutheran fire and brimstone.) I hate fire and brimstone, and this chorale downright frightens me.

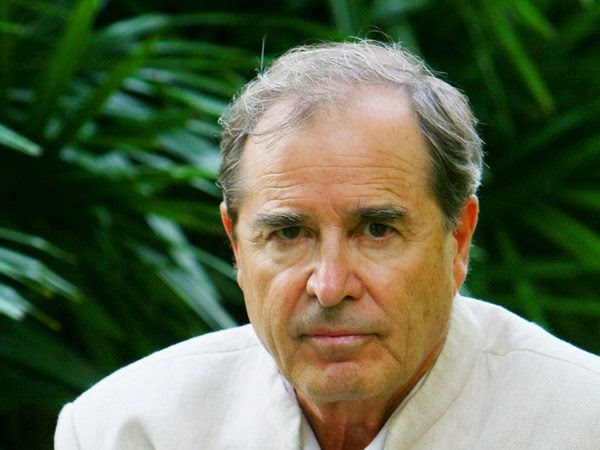

If it must be so ...... If we accept Richard Flanagan's premise in his Booker-winning novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North .... then we really have no control. Larger forces are always in play, and those forces make our own efforts futile. We struggle, we try, we love, we fail. It's all in service of larger forces that we cannot and probably should not try to fathom. The book is a wonderful and painfully poignant representation of that fatalistic point of view, though I strongly doubt that Flanagan actual espouses it.

Cruelty, love, violence, sensuality ... it's all the same, all a manifestation of unknowable controlling forces combined with biological inevitability. We simply play out the hand we're dealt.

I very much admire this book. I very much dislike the outlook that this book represents. If this really is life, then 'check, please'. But the representation is fascinating and captivating. I live in Silicon Valley in 2014, where failure is simply a rest area on the way to success, where cash is sloshing around looking for a home, where real estate valuations are more insane by the day, where programmers have agents, where life is good for many. The novel portrays the plight of allied POW's in Burma forced under terrible duress to build the Burma Railway of Death. Thousands of lives lost under brutal conditions. But that plot line is just the most radical manifestation of people caught up in larger forces beyond their control. Love, war, family, illness, accident, fire ... they all are beyond our control, yet seemingly part of a larger pattern that we can only imagine exists ... that we actually must imagine exists. We must simply assume that it exists and go on.

Flanagan skillfully weaves in traditional Japanese haiku as well as 19th-century British poetry. In his hands both seem to resonate on similar wavelengths despite the cultural disparity. Yes, the plot is a little contrived here and there. The writing is superb. This subject matter is full of pitfalls, and Flanagan navigates the waters with aplomb. There are some thrilling moments, some lyrical moments, and very few thuds indeed.

I'll quote the rest of the chorale here, though the philosophical point of reference is quite different. Nonetheless, every time I think of this text I shudder. And my most important reaction to the book is to shudder in a similar way.

Solls ja so sein, Daß Straf und Pein Auf Sünde folgen müssen, So fahr hie fort Und schone dort Und laß mich hie wohl büßen. | If it must be so, that punishment and pain must follow after sin, so go on (punishing) here and be merciful there (in the next life) and let me well suffer here. |

Awful thoughts, inhibiting and oppressive thoughts. Downright scary thoughts. A scary book. I so hope it isn't true. But I must consider the possibility.