It’s a short book. It’s clearly in part autobiographical. Yet it’s presented as fiction.

It describes present-day Nigeria, but it’s really about

various uses of language, some to express, others simply to deceive. Indeed expression may be at least in part

always deceptive. Like memoir presented as fiction. What is true and what is not? Can there be such a thing as truth?

Cole represents Nigeria as a country riddled with corruption

and deception. From internet scams to street crime enabled by verbal intimidation

to false history to willful misrepresentation and honest attempts at

communication that inevitably fall short.

It’s all language, and language is inherently manipulative. There are

some hopeful signs in Nigeria. They are

mostly in the arts (yes, the magical and deceptive arts), and they have their

own limitations.

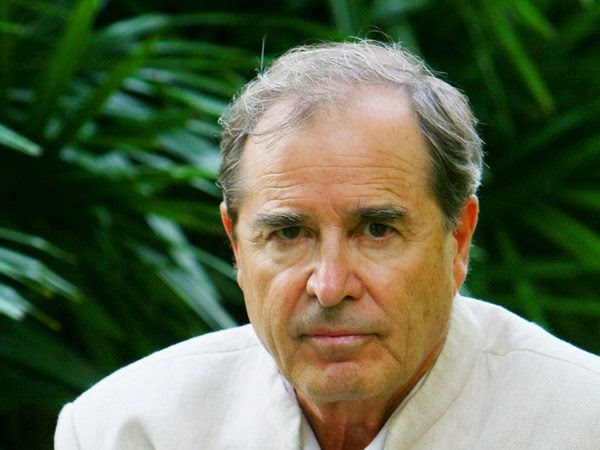

And then there are the author’s black-and-white photos interspersed

here and there in the text. What place can photos have in a work of fiction? The author’s photos? They further obscure the line between documentation

and fiction. They are blurred and unclear, subject to the interpretation of the

viewer but also suggestive representations of portions of the text. But they’re photographs (not drawings or

paintings).

|

| A representation of Teju Cole |

Cole seems intent at exploring a gray zone where all must be

questioned, and where there are no absolute answers. He brings much of the ambiguity and resonance

of poetry to his prose. The writing is

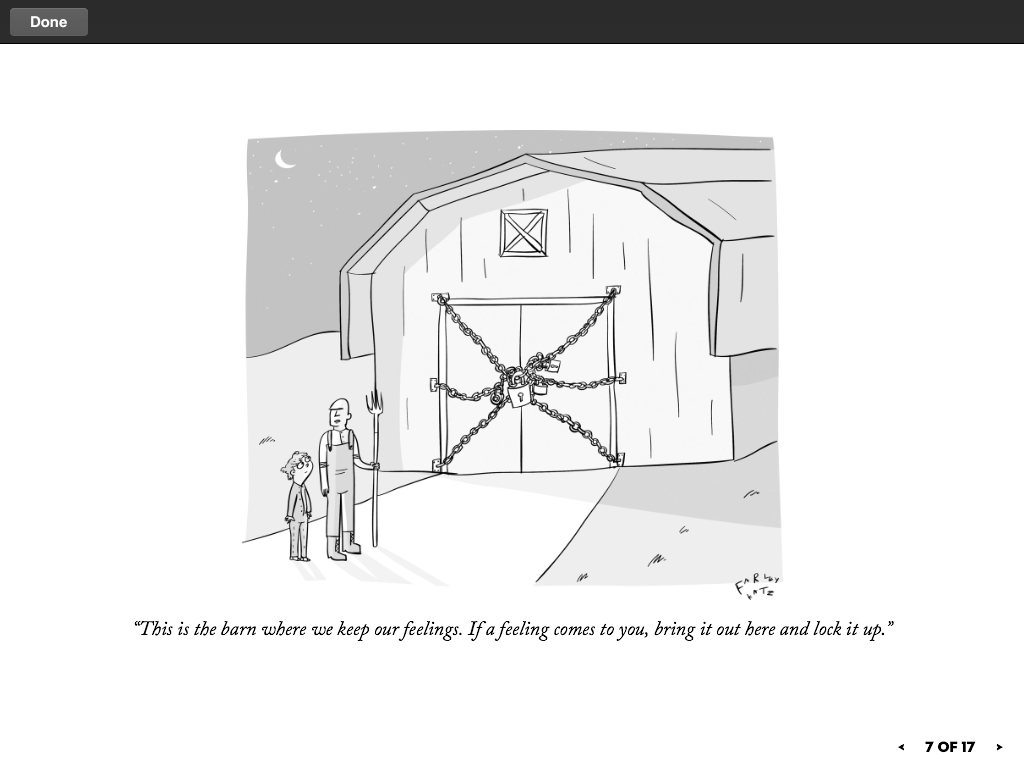

clear and plain, and that also is part of the deception. Like the acquaintance that says “I’m just

tellin’ you how it is, man”, it’s hard not to trust him. But part of his point is that nothing can be

believed, nothing can be taken at face value, we all seek to deceive one

another, we all willfully misrepresent.

What makes the scam work is the false modesty, the appearance of

trustworthiness, the veneer of truthfulness. And the resulting isolation.

Ultimately the main character can only rely on himself, his

own values (even if conflicted and very privately held), his own

preferences. I guess Freud would quibble

with even that, but that’s all Cole has. It’s lonely and disheartening to think

that any human communication or connection is in part deceptive. Are we all

just authors doing our best to create in a world where publication must always

include misrepresentation and skepticism? Perhaps.

Should that be the case, I take solace in deception: the deception of honest communication, in the false comfort of empathy, and in generous caring for others. Works for me. Don't really care all that much if it's true. It’s my story and I’m stickin’ to it.

But it is a story.